I recently moved clinics, and I now see soldiers in the morning for “sick-call”. This means that they have an acute illness (strep throat, ear infection, diarrhea- not the things I see/treat) or injury, and need treatment sooner than the next available appointment. More and more I am finding that patients and healthcare providers really don’t understand the difference between an acute injury and an acquired inflammatory disorder, which can lead to confusion, mismanagement, and ultimately delayed treatment/improvement.

An acute injury happens in one of those moments that you KNOW you did something bad- a nasty ankle sprain, dislocating your shoulder after face-planting on the slopes- and you collect your sad, mangled body to go cry on the couch. There was probably blunt force or extreme motion applied to the joint, and the moment is quick, dirty, and traumatic.

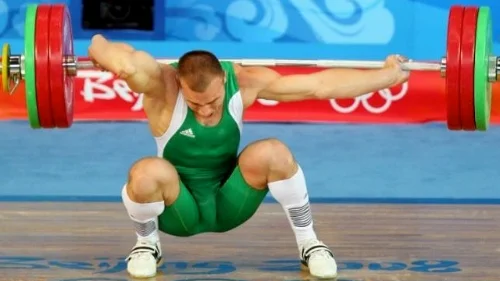

acute injury. elbows shouldn't do this.

A much different mechanism of impairment is the kind I see more frequently- a slow, steady increase in pain or dysfunction that eventually is painful or limiting enough to force you to seek treatment. This type of pain is caused by an acquired inflammatory disorder of mechanical imbalance, and is NOT the same as an injury. Understanding the difference between these two mechanisms of pain is important. The first type- an acute injury- can be something that is only treatable by surgery in extreme cases: an ACL tear, labral disruption, grade III hamstring tear. In less extreme cases, I can only really treat the symptoms until the injury is less painful, and at best try to discern why my patient experienced the injury in the first place (see: RG3’s continual ACL tears). Often times, these injuries are just plain bad luck. Maybe some jerk slide-tackled you in your rec soccer league, or you maybe you slipped on a banana peel and tried to break your fall with an outstretched hand. There is sometimes no rhyme or reason to these injuries, and I can only try to help you put your humpty dumpty pieces back together. Luckily, these acute injuries are much less common.

Anatomy of a future injury. RIP ACL

More often, I see the type of pain that is completely treatable, and even preventable. These types in issues have no clear mechanism of injury, and are brought on by a continued pattern of imbalance that eventually makes your body say “enough!” The body is designed to be in balance; abdominals balanced with lumbar muscles, adductors balanced with abductors. When one side is not pulling its weight (literally! Ha), the other side is forced to work harder, until it begins to experience an overuse-type dysfunction.

Being able to identify the muscles that are out of whack is where I come in, but first I need to understand how your pain began so we can develop an effective program for you. If this muscular imbalance issue sounds like something you have going on, being able to describe the problem is key to a quick recovery.

Make sure you emphasize to your provider that there was NOT an injury. There was no one moment in time that led to your symptoms. I can’t say how often I have patients tell me that they injured themselves while running. A lot of providers write this down, and assume the patient meant that he/she maybe rolled an ankle while running, or twisted a knee. Really, what the patient means is that it HURTS while running. A good description of pain while running would be “I have recently increased my training volume. I’ve noticed a nagging pain on the inside of my knee if I run over 2 miles over the past month, and it’s been getting more intense lately.” From this, I understand that you aren’t describing a traumatic injury and quickly know we will need to look at your running form - I don’t need to waste time searching for a damaged ligament.

Be able to describe the things that consistently bring on your pain. For some people, this is squatting or deadlifting because they aren’t engaging their abdominals enough and over time their lumbar muscles have been overused and abused. This doesn’t mean they INJURED themselves while squatting/deadlifting- that is a totally different treatment route.

Don’t get offended if your provider tells you that you may have a weakness. 80% of my patients are dudes, and they have a really tough time hearing this from a woman. They get defensive and assume I must be wrong about their pain, because they can squat 400# so they clearly are NOT weak. I recently had a guy in my office with lumbar extensors wider than my arm, but he sure couldn’t maintain a hollow hold position for 5 full seconds.

Strength does not equal large muscles.

Muscular imbalances are much more treatable than injuries, but be warned that results can take some time. Pain and dysfunction from an imbalance can come on slowly, and be slow to improve. Neurological changes in muscle strength can occur within one week as your brain gets better at recruiting muscles, but actual morphological changes, i.e. muscle growth, can take up to six weeks. Once you begin to strengthen your weak areas, imbalances should improve and your tired and overworked muscles can finally catch a break (but hopefully not literally)!